Distributed source code management has given many beautiful possibilities to orchestrate how we work. It has expanded our toolset with easy to use pull requests and generally, in my opinion, has eased up the way we can inspect the code changes. Yet, we still battle with one thing: aesthetics.

I have to confess: From the distributed league of tools, I’m only familiar with Git. I know some of Mercurial and few others. but I’ve mostly worked with Git. Like the majority of the people I know. So the things I’m going to state, reflect the experiences I have with it.

History

The absolutely best part of Git, is the ability to play with history. Like the most informative guide of Git tells us, Git is mainly playing around with graphs and their relations, which come together as the history of your repository.

The ability to rearrange that history by your whim gives you tremendous power. That’s something not to be afraid of, albeit some of the sites you find from the internet still warn you not to use even the simplest things that do so: like rebase.

You are not to believe such things: History is yours to tamper with! But only as long as you’re the only one reading it.

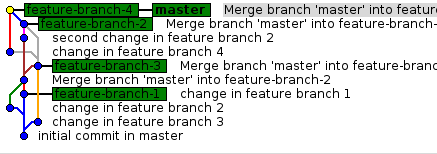

If you never rebase, your Git history starts to look less than ideal. And most likely not very truthful

Wrap it up nicely

I’m on the camp that thinks about aesthetics when looking at code. Thus, the diff and changeset that I’m going to push matters. And not just because it pleases me, but because I usually work with other people, and we do reviews. I’d want them to have it go easy.

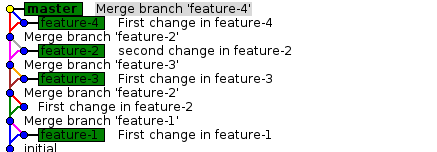

By great margin, the most common workflow I encounter nowadays is the one where people do merge/pull requests from topic/feature branches to a master branch.

With rebase used in topic branches, and –no-ff used when merging to master, you get quite nice visual view on what has happened in repository. And in addition you see what has been build upon what with single glance.

The form “request” should tell one a lot: It’s something you make for others. And indeed, every diff you have in a repository is something that others read. It’s a unit. something to figure out. Something that should explain something. Usually it consists of a log entry and a diff between changed content.

You easily pile up hundreds of commits. In that regard, it makes sense to treat the changesets with great respect. For most of us, nothing spells respect like few bullet points, so here you go, this is how you should form your log message:

- Keep the subject line width at around 50 characters

- Empty line between subject and explanatory text

- wrap explanatory text to around 72 characters (nicer output on Git log command).

- When writing, some like imperative form (“fix something”), but I have to say that I’m more fond of present tense (like “fixes something”). When merging etc, that is more pleasant to my eye.

tbaggery has some nice insights about these things.

Tell a story

Your project has a history, it might as well be a story. The thing is, we’re surrounded by different systems that want to take control of our development efforts. Different issue / work management systems like to offer ids and things that seem like an easy way to map things together.

Don’t. Don’t use them in commit messages. At least not only them, since that rips out the power of the most simple and powerful tool in our disposal: Git log.

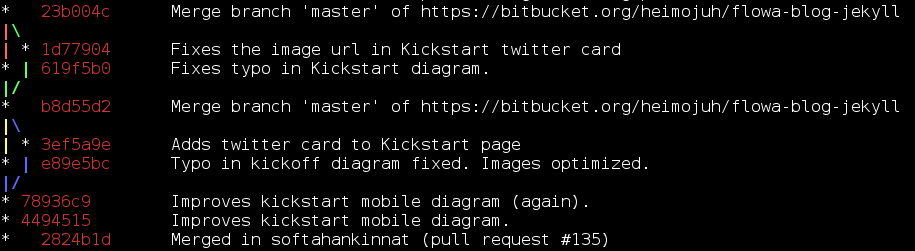

git log is stupidly powerful. Granted, there are graphical ways to inspect the history of repository, but once you get to know the options that are available with git log command, you will have the ability to examine the repository faster than ever. Above output is excerpt from command:

git log --graph --full-history --all --color --pretty=format:" %x1b[31m%h%x09%x1b[32m%d%x1b[0m%x20%s "]]]

Instead of arbitary identifiers, why not tell a story? Every commit has an intention. There is a reason why a change is made. Even if you would just be removing dead code, or fixing whitespace issues, it still serves a purpose which is well worth documenting.

Then there’s the action. The things that the commit changes, which usually are visible through diff, but it’s often useful to have some kind of an overall explanation. Especially if the length of the commit is over around three lines.

My commits often log two paragraphs: one of the intention, what answers the question “why” and then some reasoning and maybe alternative options for implementation.

The commit message that reflects this blog post (we use Jekyll and manage this whole site in a Git repository) could be something like this:

Adds VCS-commit and changeset -blog post It would be worth the effort to raise some discussion about the form of how we treat source code. So here is a short and opinionated post. Additionally includes a scss file for inline commit messages

Deliver

The things we are working on take a decent amount of our brain capacity. With Git there’s no reason to couple changes with perfectly formatted commits at the moment the work is actually done. Personally, I’m rather messy in my ways and generate plenty of commits I do not want to push.

So the actual way how we work with our source code has terribly little to do with the things we actually deliver. And yet again, we should remember that we deliver things for others to read!

This is where the ability to mangle with Git history comes super useful.

You already know about rebase. You want to rebase from master to feature branch, merge from feature branch to master. Trust me. You don’t want to do it any other way around (unless you’ve agreed on working otherwise, but this is by far the most common way to deal with feature branches).

But do you know about squashing? Of course you know. It’s about merging multiple commits to one.

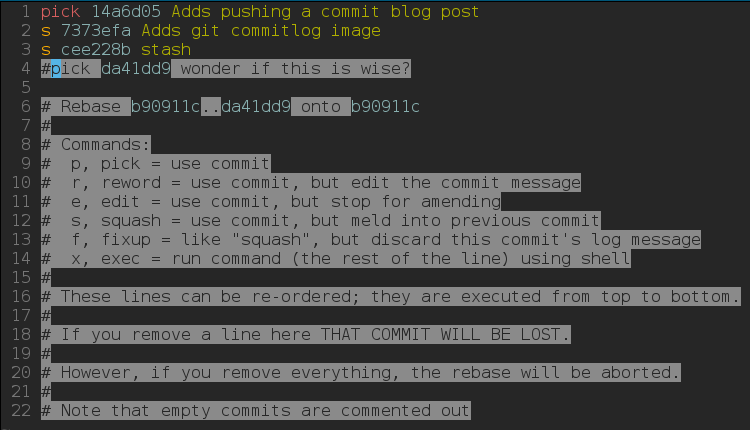

But do you know about rebase -i (interactive)? Maybe not. I find it the single most powerful command when it comes to mangling with history. You see, you don’t often work with many people on a feature branch. Of course there are cases when you do, and then you should tread carefully not to mangle with history. But usually, rebase -i is your dear friend. It allows you to rewrite history, and at the same time combine changesets to one, drop some, and what not.

git rebase -i command is essential in my workflow. I use it when working in feature branches (or in any branch with limited set of other committers). Above image is a very real situation for me. There I squash a few commits together and remove one. As you can see, the state of my feature branch isn’t always very clean. With rebase -i I can make it so, by modifying history. Also take a note that git explains quite clearly the options you have. As it usually does.

Review

When working in a feature branch, I can easily be around 10 commits ahead of master. And I have to confess, some of the commits only state “foo” or similar things, they’re just something I’ve committed just to have a revert point, etc. This is where rebase -i comes handy: I usually end up with two or 3 commits with nice descriptive log entries. It’s something that is pleasant to push, pleasant to deliver for others. And something that often is possible to separate to a few reviewable pull requests.

I’d rather have people spend 1-3 minutes per review, than 15.

When I get feedback from a review, if it’s something minor, I may amend it. Which adds it on the same commit as the current head. Or: I make a commit and then rebase -i it to the correct change. But what I DON’T do is that I make a commit that starts with “Based on review…”. It’s all the same deliverable you know.

What we aim to do, is to keep the deliverable clean, and readable. Someone will read it. And someone, at some point in future that we can’t predict, will need that information badly.

The changesets are your deliverable. Keep them clean and treat them with respect. You have the tools, so you might want to have a few moments to fiddle around with them.

If you would like to up your game with Git, I’d be happy to help! Just holler me by email juha.heimonen@flowa.fi or evilbubu@twitter!

This was me, how are things working out for you?

Source-code control is a touchy subject. We all have our preferences and these are mine. Or what I currently think and have experienced to work out fine. But no codebase, no development team, is the same, so you might have totally different constraints, and opinions.

That is more than fine. You want to merge from master to topic occasionally when working with multiple people on topic? Go ahead. The trick is to keep things clear between everyone working with the codebase!

It’s pretty much as simple as that. But I heavily suggest to review the practices every now and then. And to make sure that everyone knows the ropes. It sometimes amazes me how little people are ready to invest in actually knowing how the source code management tool works. After all, most of us work with the same tool longer than with the same language.

With any tool you can’t get rid of the communication aspect of our work. But keeping changesets clean and informative you greatly help the communication process, especially when debugging problems and finding causes for things.

Final words after the final words

Whenever I speak of Git, I feel forever indebted to Tuomas Kareinen. Less than five minutes after my first push on a shared project I learned the importance of History.